Original Title: Jeder stirbt für sich allein (Every Man Dies Alone)

‘In other words, the Quangels were like most people: they believed what they hoped’.

A longer than average review, but then I’ve had two years to formulate opinions about this book!

Well, it has certainly been an odyssey of a read! After a friend’s insistent recommendation, I read about a hundred pages in 2018, then picked up something else and forgot all about it. Even once I’d restarted last February, it still took me the best part of 2020 to finish and yet, although the lengthy reading period implies otherwise, I genuinely enjoyed Alone in Berlin.

This novel is, in a word, dense – not what I would classify as a light read, in either theme or style **. Due to the amount of detail and the complex, interlocking plot lines, it’s hard to read short bursts – it takes at least a chapter each time to re-absorb yourself in the story. Having said this, with the best will in the world, the density can make it difficult to attempt larger sections! It’s a semi-fictitious work, based on the true story of Otto and Elise Hampel, reimagined in the novel as the Quangels.

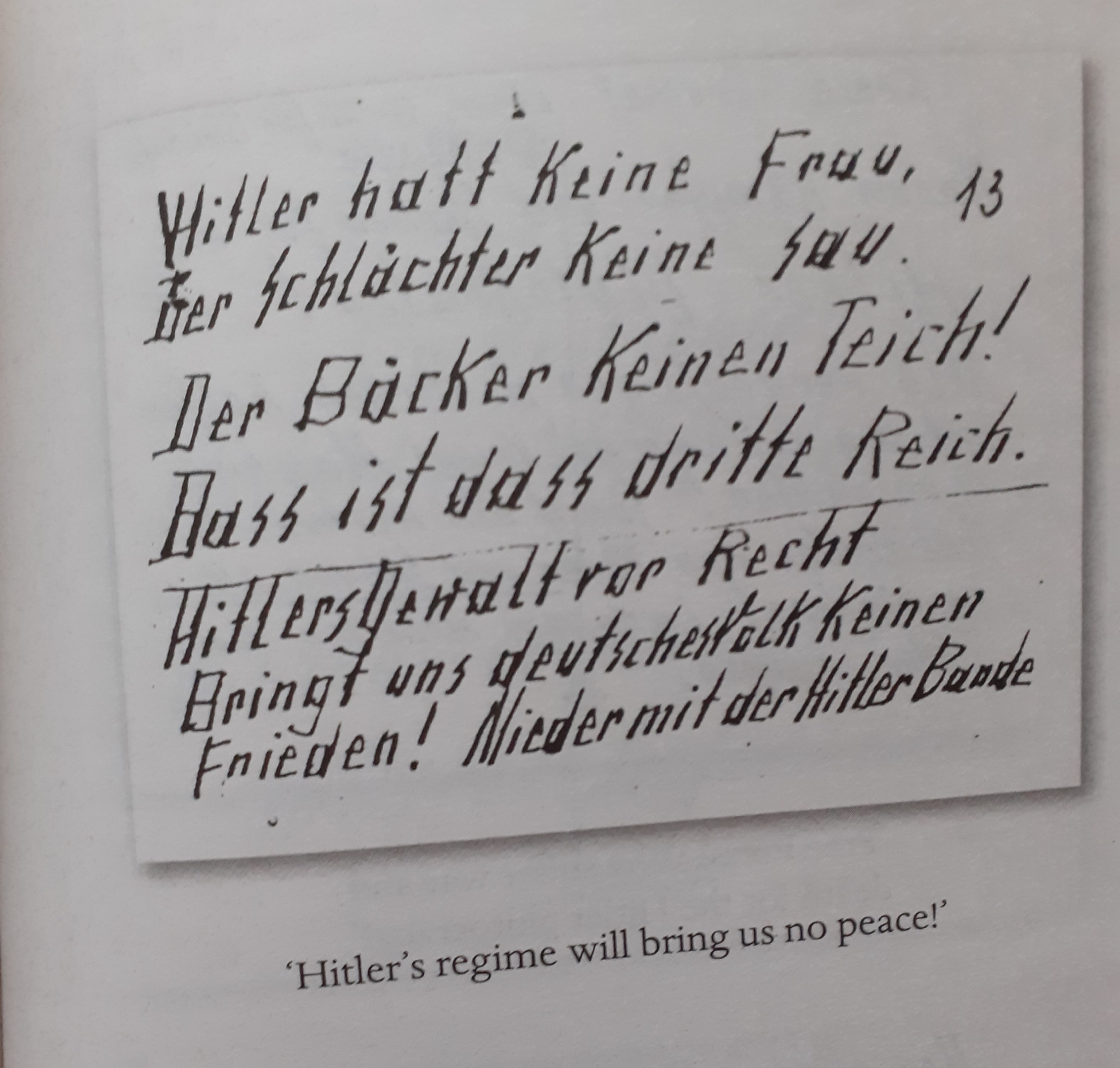

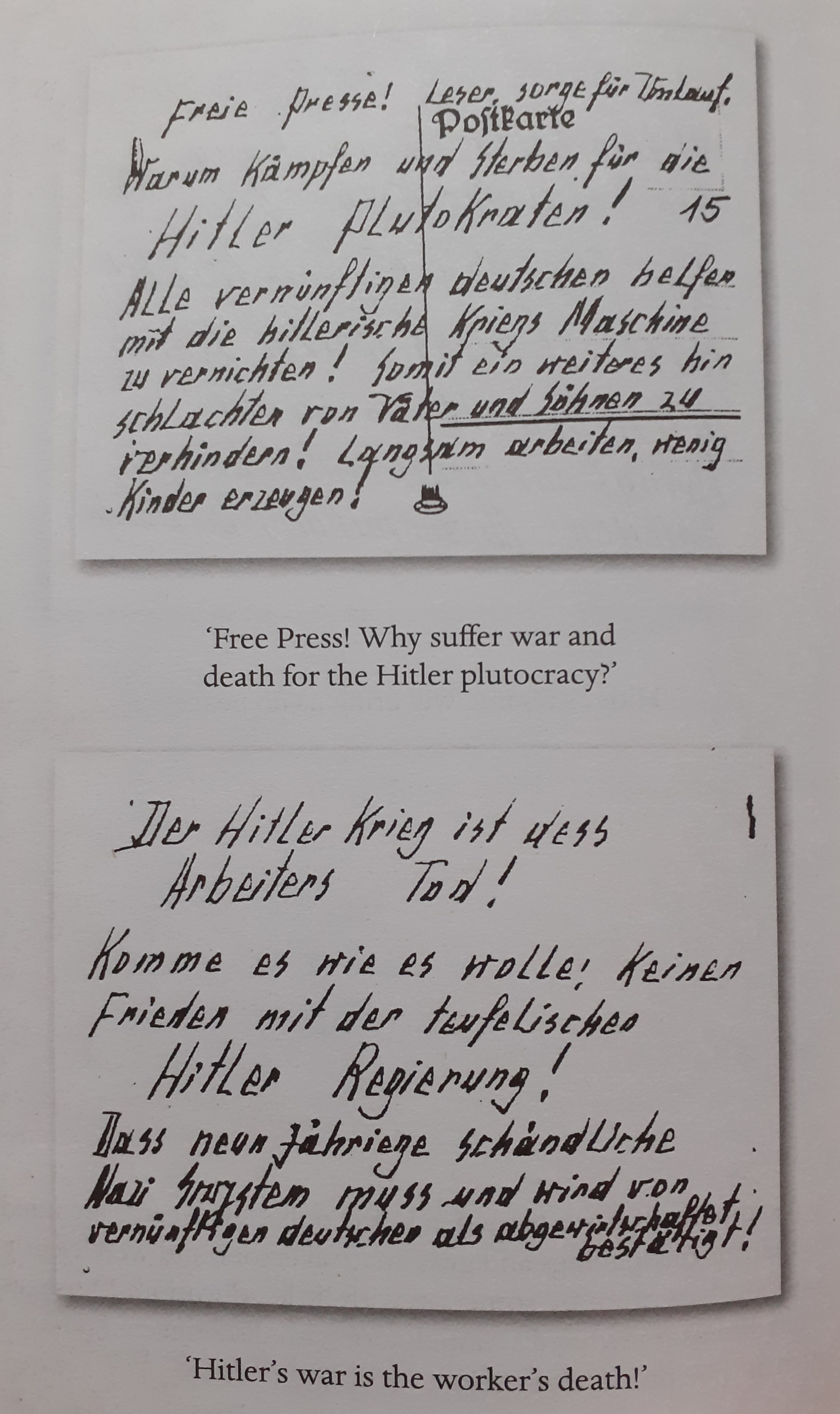

Otto Quangel is a quiet, unobtrusive man – the word ‘laconic’ is used repeatedly – living in Nazi-ruled Berlin during World War II. He and his wife Anna are content with their inconspicuous lives, careful not to do anything that might disturb the peace of their quiet, little flat on Jablonski Strasse. But when they receive news from the Front of their only son’s death, the couple are spurred into action. Otto begins to write anonymous postcards criticising the regime, dropping them in public buildings around the city with Anna’s assistance. Soon, this illegal activity catches the attention of Gestapo Inspector Escherich – ‘A man so dry, you could easily take him for a creation of office dust’. And a deadly game of cat and mouse begins …

The life of the Quangels is just one thread of the narrative, intricately interwoven with those of their neighbours, colleagues, Escherich himself and incidental characters caught up in the events. Hans Fallada tells these stories with shrewd, journalistic observation, presenting brilliantly clear insight of daily life in war-time Berlin. His descriptions, littered with humour of the most steadfastly deadpan variety, detail both the mundanities and little quirks of human nature, using a broad spectrum of characters to do so: from a pet shop owner to a Gestapo officer to a gambler. By providing this societal cross-section, the novel effectively demonstrates that no one dealt with the pressures of living under such a regime in exactly the same way. Judge Fromm chooses nocturnal isolation, just as Trudel retreats to her home comforts. Hetty copes through dissenting thoughts, but they remain just that, while one factory worker puts his treacherous sentiments into action, mangling his own hand in an act of sabotage. Naturally, their stark contrasts are interesting. However, arguably more compelling is the way Fallada uses this range of characters to show one consistent parallel; everyone, including those in positions of power, has something (or someone) to hide. For many, this is simply their unvarnished thoughts, as potentially dangerous as any crime – ‘thoughts were free’, they said – but they ought to have known that in this State, not even thoughts were free’. This widespread concealment could explain the ‘turn a blind eye’ behaviour of the public that pervades the novel; few people are willing to help others, due to the risk of drawing attention to themselves, thus exposing their own secrets.

Thoughts are a critical aspect of this novel. Although written in the third person, Fallada’s ability to write a convincing, rounded internal perspective is second to none. He uses tangential characters as onlookers to give wider context, generally remaining neutral and allowing the reader to draw their own conclusions. This complete description argues the point that no one character is wholly good or bad; each has thoughts that may betray their admirable ideals, or redeeming qualities that undermine their malicious acts. You understand their thought processes and subsequent actions, though you might not agree with them, because of the way they are written. However, the author does not hesitate to also hold his characters accountable or condemn them if necessary, reminding the reader throughout of his protagonists originally flawed beliefs.

‘Things that when they first has happened had struck them as barely censurable, such as the suppression of all other political parties, or things that they has condemned merely as excessive in degree or too vigorously carried out, like the persecution of the Jews …’

There are so many well-known novels set during this period of history (Goodnight Mr Tom, The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, The Tattooist of Auschwitz to name a few) but the particular outlook of Alone in Berlin is one I had rarely considered. As Roger Cohen observes, ‘what Irène Némirovsky’s “Suite Française” did for wartime France after six decades in obscurity, Fallada does for wartime Berlin.’ Though the novel incorporates both overt resistance to the regime (Grigoleit) and fervent collaboration (the Persickes – albeit for their own egocentric ends), for the most part the narrative focuses on the middle ground. Its characters, whatever their hidden opinions, mostly live in fearful compliance, uncomfortably aware of the perpetrated atrocities (both witnessed and rumoured) but unwilling or unable to raise their heads above the parapet. Survival seems to be the day-to-day mode of existence throughout the book. Even those initially willing to straddle the line of legality to help, by forging medical notes or sheltering politically dubious individuals, swiftly retreat once the personal risk becomes too great.

This ‘survival instinct’ is the initial position of the Quangels; Otto is an exemplary survivalist, offering no opinions and avoiding loose talk by barely uttering a word. However, with the death of their son, the desire to fight becomes stronger. The couple’s awareness of their actions’ severe consequences is referred to several times, yet they continue with steely, measured determination. This being said, they are careful. Otto particularly understands the need for longevity in their muted resistance; the more postcards they can write, the further their message will spread. Unfortunately, the perspective of Escherich brings a strong sense of dramatic irony; the reader knows the cards are not having the effect the couple imagine. They appear to have overestimated the general population, or perhaps underestimated the potency of fear and, though not entirely alone in their beliefs, most of the cards are immediately handed to the Gestapo. If anything, the finders are angry to be endangered by the unknown writer – ‘dragging strangers to the gallows!’. One of the poignant moments of the novel is Otto discovering this. Yet, as Richard Flanagan observes:

‘[This novel] suggests that resistance to evil is rarely straightforward, mostly futile, and generally doomed. Yet to the novel’s aching, unanswered question: ‘Does it matter?’ there is in this strange and compelling story to be found a reply in the affirmative. Primo Levi had it right: This is the great novel of German resistance.’

Alone in Berlin offers a profound sense of time and place. The setting is immersive, the fear and tension is palpable, with every conversation a game of Russian Roulette. The fact that Hans Fallada (born Rudolf Ditzen) was a contemporary writer adds gravitas to this conveyed atmosphere of distrust and his personal context is an important factor. Fallada’s experience of the regime was convoluted – he had been both incarcerated and institutionalised during the period, all the while struggling with a morphine addiction. Though many writers and intellectuals fled Germany for their own safety, he refused to do so, despite having been blacklisted by the Nazis. Overall, the book’s portrayal of life in wartime Berlin is damning, sometimes directly so – ‘in the year 1940, he had no yet understood, our dear Harteisen, that any Nazi at any time was prepared to take away not only the pleasure but also the life of any differently minded German’ – but for the often more subtly. Yet, when given the Hampel’s Gestapo file by a friend, Fallada initially did not wish to write about it, arguing that he had not fought back and had even cooperated with the Party. Eventually, his interest in the psychological aspect of their story took over and he completed Alone in Berlin in just 24 days, dying a few weeks before it was published in 1947. It wouldn’t be translated and re-published in English until 2009, sparking a resurgence in popularity but it remains one of the very first anti-Nazi novels to be published in Germany after the Second World War.

A lengthy but worthwhile 4 star read for me. Now on to something a little bit lighter!

** NERDY SIDE NOTE: One interesting aspect for me (admittedly probably not for anyone else…) was considering this density as a side-effect of translation. The occasionally long, slightly clunky sentences might hypothetically be due to the novel being originally written in German? Every now and then the phrasing is slightly unnatural in English; I know from learning German that sentences can be quite complex, with phrases layered on top of each other. Or it might be that the translation is entirely true to the original text and that is just Fallada’s writing style? Just a thought I had. I find translation fascinating; the little nuances can change the feel of every sentence, which is also what makes it so difficult! Wishing I read German well enough to answer my own question, but that day is far away!

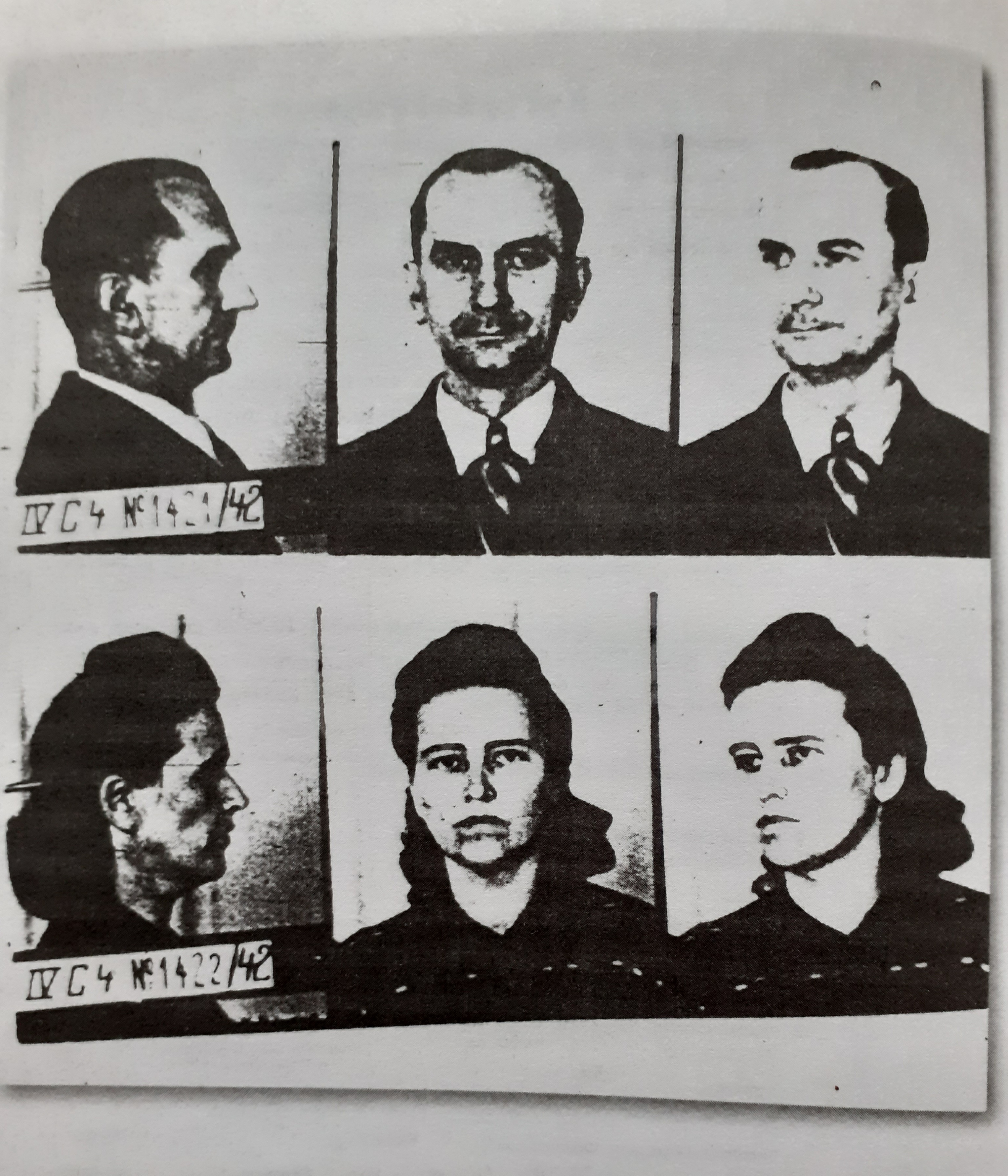

Photos from the Hampel’s Gestapo file, including images of the original postcards.