It is seldom that I’ve read such a short, simple book that has stayed with me so persistently after the final page.

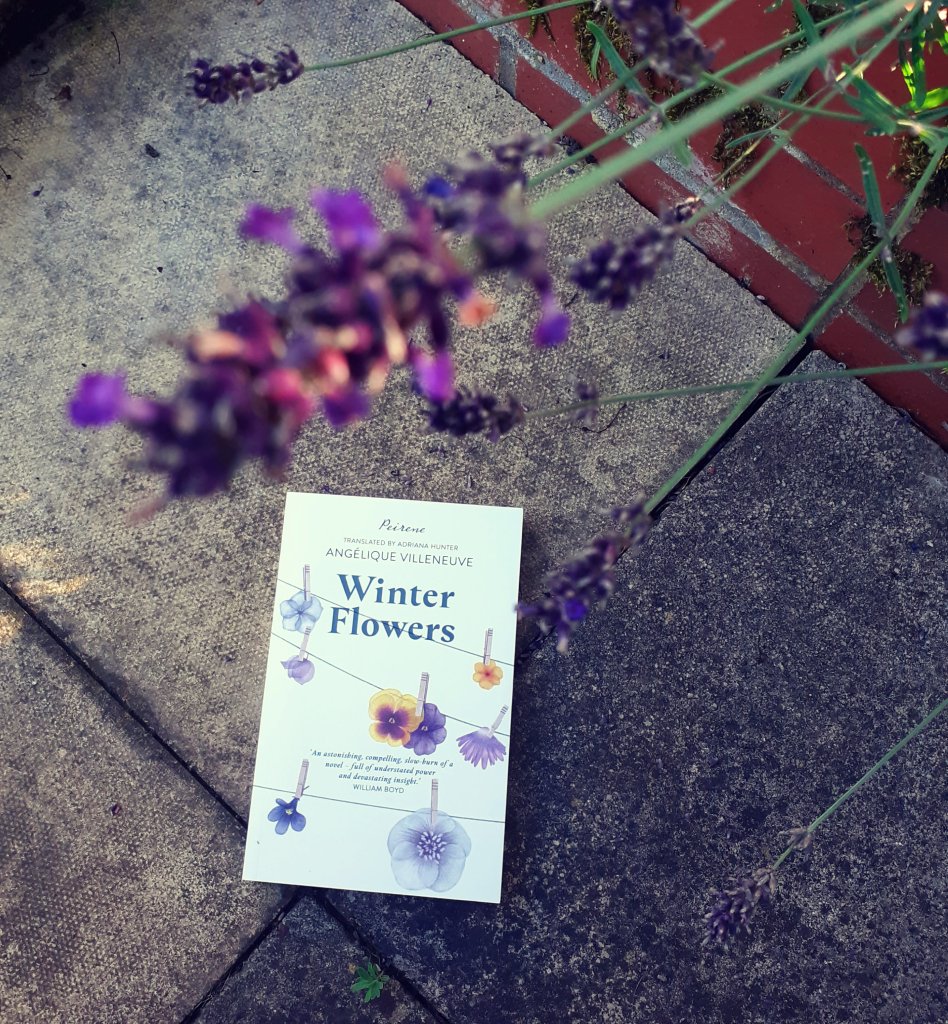

Winter Flowers (Les Fleurs d’hiver), translated from the French by Adriana Hunter, is a subtly nuanced family drama, set against the backdrop of war-stricken Paris. For two years, Jeanne Caillet and her young daughter Léonie have lived alone within the walls of their small apartment, surviving food shortages and bitter winters on the paltry sum Jeanne collects for the exquisite artificial flowers she crafts.

‘When making flowers, Jeanne metamorphoses into an incredibly self-possessed creature whose focus, skill and attention to detail enthral anyone who has the opportunity to watch her work. She can make 900 cowslip flowers in a day. Her hands produce improbable tea roses as opulent as lettuces, explosive swells of petals speckled with a shimmer of blood red or cherry red. She conjures up clusters, stalks and ears, umbels and flower heads, all more beautiful and more real than the real thing.’

The return of Toussaint, her husband, from the facial injuries ward of a military hospital unsettles this difficult but established routine, bringing new challenges and conflicting emotions into their lives, as they must learn once more to be a family of three. For Jeanne in particular, overwhelming relief is distorted by frustration, confusion and hurt. Guilt contributes to this precarious cocktail of feelings in the wake of her neighbour, Sidonie’s, tragedies and palpable fear courses throughout the novel, intensified by stark reminders of brutal wartime realities.

In my opinion, the real triumph of this novel is its simplicity; the plot is as delicate as the silken flowers that pass through the flower maker’s hands. Significance is woven into the fabric of the book not by dramatic events but by the characters’ emotions, most of which are speculated by Jeanne; though third-person, the narrative threads centre around her thoughts.

One motif I particularly enjoyed was the parallels drawn between Toussaint and the flowers. His eyes are ‘of a blue that hovers between nigella and chicory’ and careful details of his surgeries are interlaced with the creation process.

‘In two separate incisions, one on the inside, the other outside, the edges of the aperture and the whole fibrous mass are excised. / Hyacinths come in soft, subdued colours: blue, mauve, pinkish and red are achieved with rinses from various concentrations of lapis lazuli, crimson lake, magenta lake or carmine. / Using a buttonhole incision made in the cheek, a scalpel is introduced flatways from front to back under the integument.’

The titular flowers feature heavily throughout, gossamer and impossibly beautiful, an focal point around which all other elements revolve.

‘Her first cornflower in silk muslin, then a peony, a camellia, a Chinese primrose, sweet peas, a hyacinth, six different varieties of rose, lilac, clematis […] and an intricately veined lily. Lolling over to one side there’s even a poppy with a contorted stem and petals in a spectacular orange, as vibrant as poison’.

Winter Flowers is the first of Villeneuve’s novels to be translated into English, having already won an array of French literary prizes. It is the fifth work Adriana Hunter has completed for Peirene, joining titles such as Véronique Olmi’s Beside the Sea and Her Father’s Daughter by Marie Sizun.

The novel will be part of the newly announced Borderless Book Club Autumn Programme, on the 21st October.

Be sure to catch up with the latest Indie Insider issue to read my interview with Stella Sabin, publisher at Peirene Press!